Personal tools

News from ICTP 93 - Features - S O Lundqvist

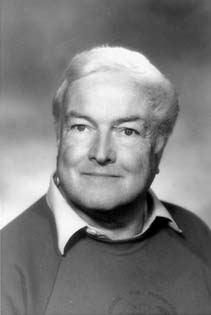

Stig Lundqvist, a key figure in ICTP's history, died on 6 April after a lengthy battle with diabetes. Friends of Stig reminisce about this unique individual, who left an indelible mark on science and ICTP.

Philip W. Anderson

Elias Burstein

Hilda Cerdeira

Praveen Chaudhari

Chi-Wei Lung

J. Robert Schrieffer

Alf Sjolander

Erio Tosatti

Yu Lu

Joyful Intellectual

I knew Stig Lundqvist from the time he became a frequent visitor

to the University of Pennsylvania during the 1960s, where my old,

really old, friends Eli Burstein (we knew each other during the

war) and then Bob Schrieffer, were. But I must admit he was only

an acquaintance. I began to appreciate Stig as a true friend and

a force in the community in June 1973, at a Nobel symposium, which

he organised at a country estate near Gothenburg, Sweden. That's

where I first experienced the good humour and the open, welcoming

hospitality of Stig and his wife. The meeting was wonderful, the

cliché phrase for it nowadays is "magical." But

it really was magical for me. Stig, through the Nobel committee,

provided a beautiful milieu and great hospitality, and the Lundqvists,

with the help of John Wilkins, brought together the right people

and the right physics at the right time. It was when the He3 story

was just breaking and the renormalization group was finally ready

for a set of summary discussions by Ken Wilson and others. Walter

Kohn was to talk about local density approximnation (LDA), and

Seb Doniach about the x-ray-edge problem.

What I didn't know then and only learned later was the great effort

Stig had-and would continue to-put forth for the condensed matter

community in breaking the resistance of traditionalists on the

Nobel committee to the new strains of condensed matter theory-efforts

that brought condensed matter to its rightful place within physics

and ultimately led to a series of Nobel prizes in the 1970s and

later, of which I was an eventual beneficiary. If I had known

this, it might, in fact, have ruined the enjoyment of the meeting

for me: I still thought of the Nobel committee as some clutch

of grizzled old elves in Uppsala, not real people like Stig, whom

you could talk to and have a drink with.

The next time I had close contact with Stig was under the best

possible circumstances, in December 1977, when I was fortunate

enough to receive the Nobel Prize. Stig was again a marvellous

host, exuding joy and good fellowship and giving you a genuine

sense that he was as happy about the whole thing as you were.

Thereafter, through the years, bumping into the joyful and beneficent

influence that Stig exerted on all those around him-despite a

deterioration in health that prevented his full participation

in my next formal visit to Gothenburg and Stockholm in 1991. Above

all, Stig was a wonderful person who took immense pleasure in

doing wonderful things for other people. He was the embodiment

of openness and goodwill-a person who derived unselfish pleasure

from the accomplishments of his fellow scientists and his fellow

men. He shall be missed.

Philip W. Anderson

Nobel Laureate 1977

Joseph Henry Professor Emeritus of Physics

Princeton University

Department of Physics

Joseph Henry Laboratories

Princeton

USA

Friend

Stig was a devoted friend and colleague, and a warm human being

with a wide range of interests and many talents: He was a jazz

musician with a deep appreciation of classical music--he played

the trumpet and arranged music for a jazz group as an undergraduate;

he was a creative chef specializing in fish dishes but, as he

often remarked, second in culinary talent to his sister Kersti;

he was a superb theoretical condensed matter physicist well-versed

in other areas of physics, making him a particularly effective

member and chairman of the Nobel Prize Committee in Physics; and

he was a creative organiser of international conferences, symposia

and advanced summer schools, enabling him to spark interactions

among physicists worldwide. In 1990, when Stig reached the age

of 65, after a long and distinguished career of service to ICTP

and full retirement from Chalmers University of Technology in

Gothenburg, Sweden, regulations made it uncertain whether Stig

would have to retire as head of ICTP's condensed matter physics

programme. Praveen Chaudhari, Bob Schrieffer and I were at ICTP

that summer for the symposium on Frontiers in Condensed Matter

Physics, organised in Stig's honour on the occasion of his 65th

birthday. We met with Abdus Salam to speak on Stig's behalf, emphasising

the important contributions that Stig had made and would continue

to make as head of the programme. Salam agreed to renew Stig's

appointment. Moreover, in full appreciation of Stig's many contributions,

he decided to award Stig a special Dirac Medal and to commit US$5,000

for a lecture series in Stig's honour to be held jointly at Chalmers

University and ICTP. Stig received the Dirac Medal at the symposium.

In 1996, an Adriatico Research Conference on Contemporary Concepts

in Condensed Matter Physics was held in Gothenburg on the occasion

of Stig's 70th birthday. Stig, suffering from diabetes for many

years and confined to a wheel chair, was honoured by his many

students and physicists from all over the world. ICTP director

Miguel Virasoro, who attended the conference, expressed appreciation

for Stig's contributions to the success of the Centre's condensed

matter physics programme and appointed Stig a distinguished ICTP

scientist emeritus. In July 1999, ICTP again honoured Stig by

launching the "Stig Lundqvist Research Conference on the

Advancing Frontiers in Condensed Matter Physics," which will

be held biennially. My association with Stig during the past four

decades has enriched my professional and personal life immeasurably.

I will deeply miss him.

Elias Burstein

Mary Amanda Wood Professor of Physics Emeritus

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

USA

Entrepreneur

Foresight was one of Stig's most striking characteristics. As

chairman of the ICTP Scientific Council in the mid 1980s, Stig,

with the support of Abdus Salam, expanded the scope of ICTP's

annual summer workshops on condensed matter physics by adding

the Adriatico Research Conferences. The intent was to discuss

exciting and novel ideas in ways that scientists unacquainted

with a particular field could understand. The first Adriatico

Research Conference on Quantum Chaos, which was organised by Giulio

Casati and Martin Gutzwiller, took place in June 1986. At the

same time, Stig also inspired a new series of events in nonlinear

dynamics, and then convinced Mario Tosi and Norman March to run

the condensed matter physics group's spring college on condensed

matter physics focusing on order and chaos in nonlinear systems.

The conference and college took place simultaneously providing

a synergism that helped elevate the presence of the Centre in

these two emerging fields. My first encounter with Stig and the

Centre came during the latter activity. I was impressed by the

interest that Stig gave to everyone's inquiries and concerns (at

the time, he not only headed the ICTP Scientific Council but presided

over the Nobel Prize Committee in Physics in Sweden). I returned

to the Centre for a lengthier stay in summer 1988. At the time,

Stig was thinking of organising a conference to celebrate the

Centre's 25th anniversary and he was looking for a person to help

him. I was lucky to be the one he chose. What ensued was one of

the most exciting summers in my career. Hours--indeed days--were

spent discussing the topics we should cover and the people we

should invite, all within the context of looking to the future

as well as the past and using the occasion both to celebrate how

far ICTP had come and examine where the Centre should go from

here. The conference proved a success. Almost a decade later,

Abdus Salam's son, Umar, noted at the Abdus Salam Memorial Meeting

in November 1997 that the anniversary event was one of the happiest

moments in his father's long and memorable career. But such happiness

was matched by growing sadness: During this period, Stig's long-term

battle with diabetes began to take its toll. Poor health sometimes

forced him to miss talks given by conference speakers whom he

had carefully chosen, as well as some of the condensed matter

physics advisory committee meetings where the agendas of the Adriatico

Research Conferences were finalised. His absence left a void in

our discussions and evaluations that no one could fill. In 1992,

at the end of the Conference on Frontiers in Condensed Matter

Physics, which celebrated the 25th anniversary of condensed matter

physics activities at ICTP, Stig resigned as chairman of the Scientific

Council. It marked the end of an era for both him and ICTP.

Hilda Cerdeira

Staff Member, ICTP Condensed Matter Physics Group

Head, ICTP/TWAS Donation Programme

I first met Stig Lundqvist about 15 years ago, when he visited the IBM Research laboratory at Yorktown Heights, New York (USA). As often happens between individuals, there was instant recognition and the formation of a bond between us. It was Stig who introduced me to the ICTP and to Abdus Salam. It was again Stig and Eli Burstein who convinced me that the ICTP was a unique institution in the world. It was the involvement of Stig, Eli, and Bob Schrieffer into the affairs of the ICTP that drew me to serve on various committees at the ICTP. As I began to visit the ICTP, I could see the impact Stig had on the institution-not just in condensed matter physics but on all aspects of the ICTP. He was chairman of the Scientific Council and in this role he helped guide the Centre in raising its quality and the strength of its organization. He was instrumental in starting the condensed matter group that has been so ably lead since Stig's time by Yu Lu and Erio Tosatti. At the ICTP, Stig was a commanding figure, nay a towering figure. He was respected not just for his contributions to our understanding of condensed matter but for his numerous other attributes: He was a member and chair of the Nobel Prize committee for physics, professor of physics and, at ICTP, chair of the Scientific Council, dean of condensed matter physics, organizer of outstanding conferences famous both for their topicality and for attracting some of the best minds in the world. Since Stig's departure, there has been no one quite like him at the ICTP. Stig had the uncanny ability to find people to help improve ICTP. His heart was in the place. He lived for the Centre and sometimes, it seems to me, the Centre became an integral part of him, almost like an extended family. It is therefore a great source of pleasure for me to see Stig's contributions recognized by the ICTP in this, albeit small way by naming a prize, a conference, and a lecture room after him. Each of these recognitions epitomize his credos: outstanding science, dissemination of knowledge, and a place where scientists of all cultural and economic backgrounds can meet.

Praveen Chaudhari

Chairman

ICTP Scientific Council

Former Vice-President for Science and Technology

IBM Research Division

Thomas J. Watson Research Center

Yorktown Heights, NY

USA

Chinese Connections

I first met Stig at ICTP in 1979 when I was a member

of the first Delegation of Solid State Physics, headed by HUANG

Kun. After his seminar, Stig had a personal discussion with me

on the problem calculating specific surface energies of solids.

I found he knew the names of such Chinese scientists as GUO Kexin,

a physical metallurgist who had been in Uppsala University in

Stockholm from 1947 to 1956 and who was the head of our laboratory

at the Institute of Metal Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences

(CAS), in Shenyang. Stig was very interested in the situation

in science in China, and he asked me many questions. In 1982,

Stig first visited China upon an invitation by GUO Kexin and myself

as the head and deputy head of the Laboratory in the Institute

of Metal Research (CAS). He gave lectures in the Institute of

Physics (CAS) in Beijing, Fudan University in Shanghai, University

of Science and Technology of China in Hefei, and visited Northern

West University in Xi'an. At that time, I was appointed an Associate

Member of ICTP, and continued to enjoy that privilege from 1982

to 1988. In the summer 1984, just one day before my leaving for

China, I met Stig again on the first floor of the ICTP Main Building.

He introduced me to the new concept on fractals and recommended

that I apply it in the field of mechanical property of metals.

A few months later, he gave me Mandelbrot's book on The Fractal

Geometry of Nature in which the author cited his first paper

on fractal description of fractured surfaces published in Nature

(1984). This paper caught my attention and I decided to dedicate

my work to this problem. In 1987, the International Centre for

Materials Physics (ICMP) was founded by the CAS with the help

of the Institute of Metal Research. ICMP emphasizes the application

of new concepts in physics to studies of materials. We were honored

by letters of congratulations by Stig and Abdus Salam, and both

agreed to serve as international advisers for this new center.

Later, in 1989, a Spring College on Fractals in Materials was

held in Shenyang. This activity was attended by more than 40 young

physicists and engineers from China. In 1985, I was fortunate

enough to become a Member of the Solid State Advisory Committee

at ICTP. Spring Colleges on Materials Science and Working Parties

on Mechanical Properties were held at ICTP every other year from

1987 to 1993. These activities proved helpful to scientists working

in materials science and technology from developing countries-providing

opportunities for interaction with such leading experts as P.B.

Hirsch, G.W. Greenwood, R. Bullough and R. Thomson. Chinese colleagues

in other branches of physics and mathematics would certainly confirm

my views on Stig's uncommon enthusiasm in assisting scientists

from developing countries in his life as a scientist in developed

country.

Chi-Wei LUNG

Professor and

Director

ICMP

Chinese Academy of Sciences

China

Scientist

Among his many attributes, Stig Lundqvist was an outstanding

scientist. He conducted fundamental studies of electron gas, particularly

the role of collective plasmon excitations in spectroscopic properties.

One particularly important study of Stig's concentrated on particle

spectroscopy. He found that a resonance occurs when the spectrum

is probed at an energy corresponding to the plasmeron energy.

The plasmeron is a bound state of a hole and a plasmon. These

excitations were observed experimentally and provide a fundamental

aspect of electron gas. Another important aspect of his work concerned

the electron tunnelling spectrum in metals. He studied the single

quasi particle and collective mode spectrum of solids, again probing

fundamental aspects of correlations in the electronic properties

of metal and superconductors. Stig also was interested in electronic

correlations at short spacing, a property poorly described by

the traditional linear response theory. In collaboration with

Kundan Singwi and Alf Sjölander, he developed an approach

that treated short-ranged correlations in a self-consistent manner.

This scheme greatly improved the charge and spin response functions

involved in tunnelling, photoemission and high energy electron

loss spectra. In addition, Stig was interested in the role of

collective behaviour of superconductors and the role they played

in preserving the gauge invariance. In these and many other subjects

he worked closely with students. He would spend long hours discussing

how to formulate solutions to complex phenomena. He was truly

a mentor who took special interest and care for those who were

fortunate enough to be part of his scientific family. Stig was

an enormously enthusiastic person who willingly shared his insights

and friendship with everyone he met. He helped bring into sharper

focus the vision that Abdus Salam had presented from the Centre's

beginning. His accomplishments and outreach to generations of

scientists and students will be long remembered.

J. Robert Schrieffer

Nobel Laureate in Physics 1972

University Eminent Scholar Professor/Chief Scientist

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

Florida State University, Tallahassee

USA

Colleague

Stig and I first met as students at Uppsala University during

the 1950s. We continued along our parallel tracks at Chalmers

University, where Stig arrived as a professor in the department

of physics in 1961, just a year before me. At the time, superconductivity

(BCS theory) and neutron scattering in solids were two 'hot' subjects.

During our early years at Chalmers University, Stig and I were

very close; we even collaborated on a paper examining many-body

theory. For me and my wife it was wonderful to have Stig and Eva

around and it was through them that we made many of our international

contacts. Stig eventually became involved in a wide range of issues

related to scientific research policy in Sweden and abroad. In

Sweden, he became 'Mr. Solid State.' Virtually no policy decision

related to the study of physics there was made without him. Despite

his many responsibilities, whenever I visited him in his office

he was never in a hurry. In fact, he always seemed to have time

to sit down and discuss any matters that were on my mind. In later

years, Stig was surrounded by a group of younger people, who were

his former students and who later assumed positions of high responsibility

at Chalmers University. Some--for example, Bengt Lundqvist (unrelated

to Stig), Goran Wendin, and Mats Jonson--have become internationally

well known. Stig was proud to have played a role in their success

and I am sure that he was equally proud of his own accomplishments,

which included more than 100 publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Yet, his importance extended well beyond mentoring and publications.

As a recent obituary in Gothenburg's local newspaper noted, Stig

was instrumental in bringing together physicists "from different

countries, from different ages, and from different research areas."

By being in the middle of the arena where new ideas were discussed,

he often played the role of ringmaster in advancing his discipline,

which was also his passion. Despite the loss of his beloved wife

Eva in 1981 and the progressively debilitating impacts of diabetes

in the last two decades of his life, he continued to inspire others

and to speak out vigorously for physics. Stig had many of the

best qualities a person can have. Those who were fortunate enough

to be within the circle of his unique personality, intellect and

drive will never forget him. Both my wife and I are proud to be

among them.

Alf Sjölander

Professor Emeritus

Chalmers University of Technology

Gothenburg, Sweden

Teacher

On a corner shelf in my living room, lies a thick physics book

with frayed pages and a faded soft green cover, once much used

but now coated with dust. Not far away on the same shelf, there's

a miniature reddish wooden horse, plain in appearance, nothing

special to look at. For me, both objects are special because they

evoke fond memories of Stig Lundqvist. The book contains lecture

notes drawn from research activities that took place in Trieste

in 1967; the horse is a present of the Lundqvists, Eva and Stig,

who visited my house just after I had come to Trieste in the late

1970s. As a freshly enrolled Ph.D. student in physics in 1967,

I was asked by my supervisor, Franco Bassani, to attend a winter

school at the Trieste-based International Centre for Theoretical

Physics (ICTP)--a place whose existence, unlike my relatively

famous "Scuola Normale" in Pisa, was then not well known.

Indeed ICTP's existence was news to me. Yet the mission of the

Centre seemed worthwhile, even noble: to bring together scientists

and students from all over the world, poor and rich countries

alike, to learn from one another in an atmosphere that encouraged

the free exchange of ideas. The winter school was not only my

first research activity; it was the ICTP's first school in condensed

matter physics. And that's exactly what made it a magical event

for lecturers and students alike: Everything took place more or

less on the spot, including finding references mentioned at talks

or during conversations, tracking down an empty desk in the library,

or even locating a special place for dinner in downtown Trieste.

In the eye of this intellectual and cultural hurricane of exchange,

this whirlwind environment of learning and friendship, this unforgettable

experience for both students and lecturers was Stig Lundqvist,

a gregarious Swede who seemed just as at home detailing the intricacies

of his 'many body theory,' which was new to many of us at the

time, as he was finishing off a beer at a local bar (yes, Stig's

Nordic roots were never far from the surface). The best moments

for many participants often came after, not during, the lectures

when Stig became even less formal and more loquacious than he

had been during the formal presentations. Stig appeared to be

one of us, only more knowledgeable, far different than the stand-offish

image we had of the big influential university professor we were

told he was. His do-good actions (Stig in fact lived his whole

life by doing good) were rarely on display in his conversations

after hours: he was just a plain-talking guy sharing a joke, a

drink, a good meal. Stig, from the first day we met, impressed

me as nothing more than a big student blessed with a big mind

and a big heart. Yet, his jovial nature often hid how serious

he was about science and about helping people. Indeed his good-natured

behaviour proved an effective way for Stig to achieve his goals.

Perhaps it worked so well because Stig after-hours was the same

person as Stig during classroom lectures and discussions. I'm

surely not alone in my admiration for this remarkable man and

his remarkable career. His continuing presence and leadership

in Trieste between the late 1960s and mid 1990s was certainly

an element, perhaps the key element, that persuaded so many of

us worldwide to come to Trieste and to ICTP as often as we could

to learn about physics, to re-establish old friendships and develop

new ones, and to participate in a learning experience that was

both edifying and enjoyable. Stig's great gift was to make physics

fun and to personalise his grand vision in ways that made everyone

who joined him in his quest to feel as if they were a part of

a glorious ride into the future... with one glorious man leading

the way.

Erio Tosatti

Professor of Physics, International School for Advanced

Studies (SISSA)

Consultant, ICTP

Statesman

In a sense, Stig Lundqvist was responsible for me coming to ICTP.

I first met Stig in China in 1983 when he visited the Institute

of Physics in Beijing, where I was a member of the research staff.

He probably had heard about me from others, including Bob Schrieffer,

the Nobel Laureate. Stig and I spoke as if we had known each other

for years. Soon after our initial conversation, Stig arranged

for me to visit ICTP, the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics

(NORDITA) in Copenhagen, Denmark, and the University of Gothenburg,

Sweden. These first encounters with Stig, in many ways, were emblematic

of the man. His extraordinary enthusiasm for new things in physics

and his irresistible warmth towards colleagues, especially young

researchers, were inherent parts of his personality. I returned

to Europe, specifically Trieste, the following year, having been

named an Associate of ICTP. While here, Stig discussed with me

the possibility of coming to Trieste for a longer period. Our

conversation took place at the same time that ICTP's administrative

oversight organisation, the International Atomic Energy Agency

(IAEA), was examining whether to permit ICTP to create a permanent

research staff--something that Stig was very keen on. Since the

Centre's inception, all researchers had come for a set period

and then returned to their home institutions. It was largely through

Stig's efforts, along with the vision and determination of Abdus

Salam, that the Centre began to build a permanent research staff.

I was fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time.

With Erio Tosatti and Mario Tosi in Trieste and Norman March and

Paul Butcher from outside, Stig was a driving force behind the

ICTP condensed matter physics programme. He was also the main

attraction for a large number of distinguished ICTP visitors,

like Nobel Laureates Bob Schrieffer, Phil Anderson and Walter

Kohn. The Spring College on Order and Chaos in Condensed Matter

Physics in 1986 was the first activity at the Centre that I was

involved in running. Some members of the ICTP Solid State Advisory

Committee apparently had reservations about whether the Centre

should invest heavily in this new research area. Stig's enthusiasm

convinced them to approve it and, thanks largely to Stig, the

activity was an enormous success. In 1985-1986, just after the

Centre received a substantial new infusion of funds, Stig proposed

the creation of the Adriatico Research Conferences, where young

scientists, particularly from the developing world, would be exposed

to fundamental aspects of the field in morning lectures and then

hear about cutting-edge ideas at more specialised afternoon talks.

At a 1987 conference, for instance, participants learned about

the scanning tunnelling microscope from the very person who won

the Noble Prize for the invention, Heinrich Rohrer. Stig also

led ICTP's efforts in 1987 to organise a conference on high-temperature

superconductivity just after the topic had gained international

attention in the press. The event, which was put together in just

two months, turned out to be the second largest gathering on the

topic in the world, eclipsed only by the so-called "Woodstock

of Physics" session that took place during the American Physical

Society meeting the same year. It was not only a first-rate scientific

happening where Doug Scalapino first proposed the idea of d-wave

superconductivity in high Tc cuprates, but it proved an important

political event. Stig managed to bring 15 leading scientists from

the Soviet Union. It marked the first time that such a large number

of Soviet-trained scientists participated in a research activity

in the West. Stig's two great qualities were his infectious enthusiasm

for researching and teaching physics and his deep commitment for

helping young researchers from the developing world. Both these

aspects of Stig's personality played a key role in the development

of ICTP. That's why his memory will ever remain present in the

Centre for years and decades to come.

Yu Lu

Head, ICTP Condensed Matter Physics Group

Stig Lundqvist receiving the special Dirac Medal from Abdus Salam. On the left, Anders Sjöberg, President of Chalmers University of Technology.

Group photo at the Symposium on Frontiers in Condensed Matter

Physics in honour of Stig Lundqvist (August 1990). Left to right:

Heinrich Rohrer, Philip W. Anderson, Abdus Salam, Stig Lundqvist,

Paolo Budinich and J. Robert Schrieffer.