Personal tools

News from ICTP 93 - Features - Iran

A recent trip to Iran by the ICTP director and two senior scientists revealed a nation that is scientifically sophisticated and eager to participate in the international research community.

Journey to Iran

As Iran continues to slowly open its doors to foreign visitors after two decades of isolation, ICTP scientists have been among the first to receive invitations.

This spring, ICTP director Miguel Virasoro and two ICTP group

leaders--Iranian-born Seifallah Randjbar-Daemi, head of the Centre's

high energy physics section, and Massimo Altarelli, head of the

ICTP synchrotron radiation theory group and chief executive officer

and science director of Elettra, the Italian synchrotron

radiation source--journeyed to Iran at the request of the Iranian

government.

The director's itinerary included a meeting with the Minister

of Science, Research and Technology; discussions with researchers

at the Institute of Physics and Mathematics; and a tour of Sharif

University in Tehran, Iran's most prominent institution of higher

education. Virasoro also visited a cyclotron facility in Karadje

and spoke to officials at Iran's National Science Foundation.

Meanwhile, Randjbar-Daemi and Altarelli were two of 15 scientists,

including the director general of CERN Luciano Maiani, invited

to attend a conference on the "Future of Physical Science

in Iran and the Region," organised by the Ministry of Science,

Research and Technology.

At the conference, Altarelli spoke about experiments with synchrotron

radiation as well as the potential value that may be derived from

participation in 'small' science projects. As Altarelli put it,

"you don't need a synchrotron to do interesting science;

less expensive lasers and tunnel microscopes often are sufficient

tools to do first-class research." Randjbar-Daemi, on the

other hand, emphasised "the importance of establishing centres

of excellence in the basic sciences as a prerequisite for building

a strong national framework in science and technology." While

there, Randjbar-Daemi and Altarelli also had an opportunity to

visit several of Iran's research and teaching facilities.

Virasoro describes the visit as "an encouraging sign of Iran's

desire to reintroduce itself to the West" after a long absence

characterised by tension and mutual hostility. "The exchange,"

he quickly observes, "was a learning experience" not

just for the hosts but for the guests as well. Although burdened

by isolation and poor facilities, "Iranian science is surprisingly

strong in a number of areas, particularly mathematics, condensed

matter physics and string theory." Sciences requiring expensive

equipment or having strong links to technology are the weakest

pillars in Iran's scientific infrastructure. "Persian culture's

dedication to education is deeply rooted," notes Virasoro,

"and that dedication remains vibrant today in all areas of

study, including science and mathematics."

"The population," adds Randjbar-Daemi, "is both

young and well-educated." In a country of 60 million people,

"there are about 1.7 million university students-a percentage

that compares favourably with Italy and other developed countries."

The large number of university students reflects both Iran's youthful

population-about 50 percent of the nation's population is 25 years

of age or younger-as well as the emphasis and resources that the

government has placed on education.

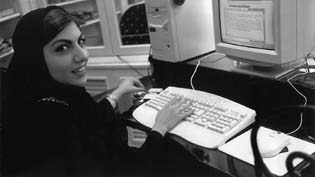

Altarelli also notes that the number of young women earning university

degrees, including degrees in mathematics and science, is surprisingly

high. Women, moreover, are not absent from university teaching

positions. In fact, the head of the Department of Physics at Sharif

University is a woman. "Iranian women," he says, "

continue to wear 'chadors,' their traditional veils. Yet, when

it comes to their quest for new knowledge, many young Iranian

women seem to be thoroughly modern."

Such promising trends in Iranian scientific research and training

do not mean that serious problems are a thing of the past. Randjbar-Daemi,

for example, observes that heavy teaching loads make it difficult

for university professors to pursue a vigorous research agenda.

"Equipment," he adds, "while adequate for teaching,

is often inadequate for state-of-the art research."

Meanwhile, the number of mathematicians and physicists involved

in research remains too small to create a critical mass of activity.

Randjbar-Daemi estimates that there are only 350 physicists with

doctorate degrees in all of Iran; Italy, on the other hand, has

awarded about 1,300 doctorate degrees to physicists since 1987.

Such small numbers, combined with heavy teaching responsibilities,

make it difficult for Iranian scientists to develop areas of specialisation.

Under these circumstances, Altarelli notes, "it is remarkable

that Iran's scientists have gained international presence in several

fields of specialisation."

But for Iranian scientists to attain more prominence in the future,

policies must be devised not only to promote the education of

talented young people but to create broader channels of communication

with the international scientific community. The latter concern

is one of the reasons the Iranian government has been eager to

encourage contacts with scientific communities in the West.

"Iran was never like the former Soviet Union," says

Randjbar-Daemi. "It's true that the government has been reluctant

to send young scientists abroad for fear that they would not return.

But there have been few restrictions on travel for more mature

scientists. The problem has been that several countries, notably

the United States, have refused to extend visas to Iranian researchers.

Hopefully, that will change in the near future."

While the Iranian government seeks to expand scientific co-operation

with other nations, it also hopes to strengthen its own university

system. "There are really only a few universities of excellence

in Iran," says Randjbar-Daemi. "And even in these universities,

meaningful reforms could make the learning environment more open,

dynamic and productive."

That's why Randjbar-Daemi, along with Reza Mansouri, a researcher

at the Institute for Studies in Theoretical Physics and Mathematics

in Tehran and former ICTP Associate, have urged the Iranian government

to radically transform one of the nation's existing universities

into a new learning environment based on more modern principles

of university governance and administration.

If successful, "such an initiative," Randjbar-Daemi

notes, "could serve as a model for other universities."

Officials from the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology

have expressed support for this 'new university' concept and advocates

are hoping that funding for this experiment in higher education

will soon be forthcoming.

"Iran is a country that may surprise you," says ICTP

director Virasoro. "Twenty years of isolation have not left

the country frozen in time. In fact, the democratic reforms that

recently have been enacted, regardless of how fragile they may

be, suggest that even more dramatic changes may be on their way."

The scientific foundation that has been built over the past few

decades has positioned the nation's scientific community to make

significant contributions to the nation's future progress.

"The Iranian people are fully aware that their nation is

at a crossroads," Virasoro says, "and science, in the

minds of the people I spoke to, is often seen as the best tool

they have for shaping the future that lies before them."

Indeed science-based policy options, such as those discussed during

the recent visit of ICTP's director and section leaders, suggest

that Iranian society and science may be ready to advance hand-in-hand

into the future.

Massimo and Paola Altarelli in Tehran

IRAN/ICTP CONNECTIONS

ICTP and Iran have enjoyed a long and productive relationship since the Centre's inception more than 35 years ago. To date, nearly 1000 Iranian scientists have visited ICTP to attend research and training activities. In addition, more than 40 Iranian scientists have been selected as ICTP Associates. Last year, the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Higher Education opened a Scientific Meetings Office that drew on the ICTP experience for much of its inspiration and structure. The office plans to organise international and regional scientific research and training activities ranging in scope from two- to three-day workshops to six-week schools (see News from ICTP, Winter 2000, p. 9). Finally, in 1992, the Iranian government's generous offer of a US$3 million bridge loan enabled ICTP to overcome the greatest financial crisis in the Centre's history. Political and economic woes in Italy had delayed the Italian government's voluntary contribution to ICTP. That, in turn, created a cash flow crisis that nearly shut down the Centre. The situation was only resolved when Iran came to the rescue.