Personal tools

News from ICTP 97 - Profile

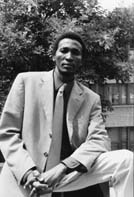

Arbab Ibrahim Arbab, assistant professor of physics at Omdurman Ahlia University in Sudan, was a student in ICTP's first Diploma Course. His road to success began in Trieste.

Sudan Success

The year 1990 was not a good

year for Arbab Ibrahim Arbab. Although he had graduated

with a bachelor's degree from the University of Khartoum in his

native Sudan a year before, he had spent much of his time since

then in search of secure employment--first in the Department of

Physics at his alma mater, where he had hoped to teach

while earning a master's degree, and then in Libya, where he taught

high school physics part-time.

"I wanted to stay in Sudan to continue my education. While

the University of Khartoum had shown some promise in the 1970s

and 1980s, by the time I was ready to begin graduate school almost

all the good people had left. Political uncertainties were making

a difficult situation even worse."

"I was running out of options," Arbab recalls, "when

my former professor at the University of Khartoum, Mohammed Saeed,

suggested that I apply to the newly created Diploma Course at

ICTP in Trieste, Italy. I didn't know anything about ICTP but

Saeed was a frequent visitor to the Centre and he assured me that

it would be a good place for me to be."

Arbab was accepted and, with 21 other young students from the

developing world, he became a member of the inaugural class of

the Diploma Course.

Arbab's first few months as a Diploma Course student were not

easy. "The courses not only proved difficult in content,"

he explains, "but they required me to think and learn in

entirely new ways. Previously I could excel by simply memorising

information. Now I had to solve problems. I'll never forget that

one of the first examinations in the Diploma Course was an open

book test. That surprised me because having the text book in front

of my eyes made me think I could look up the answers. Nothing

could have been farther from the truth."

Arbab also credits the Diploma Course with teaching him how to

teach. He notes that for the first time in his life, he was "required

to make oral presentations and to defend his arguments before

his peers," helping him acquire the organisational skills

and gain the confidence that he needed to be a good teacher.

After adjusting to the rigours of his new environment, Arbab enjoyed

a successful second semester and was among those who received

ICTP's first Diplomas. "It was a proud moment for all of

us. We had come from many different countries and cultures and

had both competed and cooperated throughout the year to attain

our goal. As members of the Centre's first Diploma Course, we

enjoyed both a feeling of individual and collective achievement

that made the moment special." Today some of the Diploma

students with whom he graduated are among Arbab's friends, including

Egyptian-born Shaaban Khalil, who is now a post doc at the University

of Sussex in the UK, and West Indies-born Surujhdeo Seunarine,

who is a post doc at Christchurch University in New Zealand.

Between 1993 and 2000, Arbab earned his Ph.D. in physics at the

University of Khartoum, where he also taught undergraduate students

first as a lecturer and then as an assistant professor. Insufficient

resources, large class sizes and poor pay made life as a scientist

difficult. "The department," he says, "lacked both

the size and energy to be a dynamic centre for teaching and research."

Reflecting a problem common to many university physics departments

in Africa, Arbab noted that the next youngest faculty member in

his university was more than 20 years older than him. He also

observes that he had to teach four classes and 200 students each

semester, leaving little time for research.

Things are now looking up for Arbab. Last year, he became an assistant

professor at Omdurman Ahlia University in Sudan, one of the best

institutions of higher education in the country. "The teaching

load is lighter and the facilities are better equipped."

More importantly, he notes, "professors are given a greater

sense of autonomy and are able to devise and pursue their own

research agendas." In Arbab's case that means time to study

and publish in the fields of cosmology and astrophysics with special

attention to questions related to vacuum decaying and fluid repulsion.

Arbab was appointed an ICTP Regular Associate in 2000 and, just

this spring, was named dean at Comboni Computer College in Khartoum.

Recent changes in Sudanese law will allow him to simultaneously

hold both his professorship at Omdurman Ahlia and his administrative

job at Comboni.

All of this means that he will now be able to meld his skills

in research, teaching and administration in ways that professors

in Northern universities take for granted.

There is no better testimony to the success of the ICTP Diploma

Course than Arbab's current good fortune. Much of this has to

do with Arbab's own skills and drive, but much also has to do

with the strong foundation in analysis, research and teaching

that the Diploma Course provided him with a decade ago.