Personal tools

News from ICTP 110 - Profile

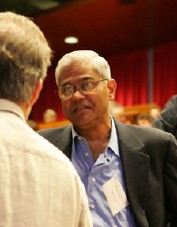

Jagadish Shukla's multifaceted career has found success across the continents both in science and service to society.

Weather to Change

In an extraordinary life and

career that began in a small impoverished village in eastern India

and continues to unfold today in suburban Washington, DC, Jagadish

Shukla has applied his diverse talents and skills over the

past four decades to scientific research, scientific institution

building and service to society, pursuing his broad ambitions

on three continents---North America, Europe and Asia.

At ICTP, Jagadish Shukla is best known for launching and then

heading the Centre's Weather and Climate research and training

activities from their inception in 1988 until Filippo Giorgi assumed

responsibility for this initiative in 1997.

Yet Shukla has also distinguished himself as a scientist who has

divided his time over the past two decades between George Mason

University in Fairfax, Virginia, where he is chairman and professor

of climate dynamics, and the Center for Ocean-Land-Atmospheric

Studies (COLA) in Calverton, Maryland, USA, a nonprofit research

centre that receives more than US$3 million in annual funding

from the US National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the National Aeronautics

and Space Administration (NASA). Shukla founded and now directs

the internationally recognised Center, which currently has a staff

of 25 scientists and 15 doctoral students.

More recently, Shukla has decided to devote a small portion of

his time and money to his native village of Mirdha, situated in

India's most populous state Uttar Pradesh, home to 200 million

people, which would make it the fifth most populous country in

the world if it were an independent nation.

Shukla's education began modestly. "My first lessons,"

he recalls, "took place in the open under a banyan tree.

In the fifth grade I attended a one-room school house built with

the help of my father. And from the sixth to the tenth grade,

I walked 10 kilometres each day to attend secondary school, where

I studied Hindi, Sanskrit and mathematics. Science was not part

of the curriculum."

A summer of intense reading of grade-school textbooks in science,

which his father encouraged him to do, allowed Shukla to do well

enough to pass the entrance examination for admission to the eleventh-grade

science class in the city of Balbia. For his undergraduate and

graduate education, he went to Benares Hindu University where

he ultimately earned a doctorate in geophysics.

Shukla was destined to lead a conventional life as a government

employee in India (upon graduation, he obtained a civil service

position in Pune) when a last minute trip to Japan to attend a

conference transformed his career. There the 24-year-old Shukla

met Jule Charney, professor of meteorology at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, USA, and, at the time, the world's most

eminent meteorologist.

"For reasons that remain unclear to this day, Charney came

to me and began to discuss my presentation. This chance encounter

with a world-class scientist ultimately led to a doctorate in

meteorology at MIT."

Shukla's studies and, more importantly, modelling experiments

at MIT and subsequently at NASA led him to a breakthrough concept

in climate predictability. "No one," he explains, "can

predict the weather beyond five to 10 days. Yet, ironically, climate

is predictable. In other words, science cannot tell you what the

temperature will be two weeks from now but science can be used

to predict what the mean seasonal temperature will be six months

from now." Shukla's investigations, conducted during the

1980s, were among the first to prove this point.

The reason that such calculations can be made is that changes

in the ocean temperatures directly affect the temperature of the

air locally as well as globally. Using a deep understanding of

the physics of climate and feeding large quantities of data into

state-of-the-art computers, scientists can integrate complex mathematical

models to simulate and predict climate variations.

"The temperature ties between the oceans and land and the

overlying atmosphere are strongest in tropical regions near the

equator, which makes tropical climate variations far more predictable

than other regions," Shukla observes. "This relationship

is a 'gift of nature' that many developing countries have not

been able to take advantage of because they lack the scientific

expertise and resources to do so."

That was the explanation Shukla gave to Abdus Salam during a conversation

in 1992 that soon led to a series of ICTP workshops and conferences

in the physics of weather and climate and ultimately to the creation

of today's Physics of Weather and Climate group.

"The initiative," explains Shukla, "was designed

both to build scientific capacity in the physics of weather and

climate in the developing world and to make the information gathered

by scientists available to countries that could then put the information

to work to improve crop yields, for example."

Soon after he relinquished responsibility for the Centre's weather

and climate activities, Shukla embarked on yet another 'adventure'

when he decided to "give something back" to the village

of Mirdha where he grew up and where most of his family, including

his brother Shri Ram, still lives.

Why does he lend a helping hand to his home village? "My

efforts are not only intended to improve the lives of people in

Mirdha but also to alter the mindset: to show people that change

is possible and that some degree of change can be good."

To advance his goals, Shukla has recently decided to devote 10

percent of his time in Mirdha, matching his previous commitment

of 10 percent of his salary.

"Giving of myself has more been difficult than giving my

money," he admits. "After five days at a house without

electricity or running water, I often find myself looking for

a comfortable hotel. Change is difficult but possible," he

notes, "and I'm the living proof that change changes us all."