Personal tools

News from ICTP 108 - Features - ICTP in the 1960s

The 1960s, ICTP's 'startup' decade, was a tumultuous time, marked by uncertainty and success. Paolo Budinich explains.

ICTP in the 1960s:

Foundations of Success

On 18 June 1964, Carlo Arnaudi, Italy's Minister of Scientific Research, and Sigvard Eklund, Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), laid the foundation stone for what would become ICTP's main building. The ceremony symbolised the creation of the Centre, fulfilling the vision first put forth by Abdus Salam four years before.

18 June 1964 Minister Carlo Arnaudi lays cornerstone of Main Building

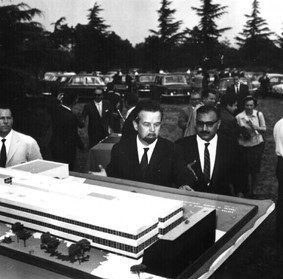

Paolo Budinich and Abdus Salam examine model of new building

The Main Building at Miramare, however, would take four years

to complete, not opening its doors until 1968. Thanks to the generosity

of the local Italian authorities, the Centre was given temporary

space in a five-story building on Piazza Oberdan, located in the

heart of the Trieste.

The building on Piazza Oberdan was not fully renovated in time

for the Centre's first major activity--the International Seminar

on Plasma Physics held in October 1964. As a result, the seminar

took place in the conference hall of the Jolly Hotel, located

less than a kilometre from Piazza Oberdan.

At the time, there was the even more compelling challenge of assembling

a capable administrative staff for a fledgling organisation with

an uncertain future.

Many of the administrative posts that remain in place to this

day were created during the Centre's first years of operation.

Indeed, by late 1964, ICTP's scientific and support staff included

a director (Abdus Salam), deputy director, scientific information

officer, administrator, librarian, secretaries, clerks, and technical

staff.

Two major distinctions, however, highlight the difference between

now and then.

Now, the staff totals 120; then, 25.

Now, long-term staff members are all employees of the UN system.

Then, staff were locally recruited under the terms of the 'seat

agreement' between the IAEA and the Italian government.

Even more importantly, because IAEA approved the creation of the

Centre on a 'provisional' basis--subject to a comprehensive review

after four years--no one was sure if ICTP would continue operating

beyond its trial run. Indeed some IAEA member states that had

supported the creation of the Centre suggested that ICTP, if successful,

should eventually be moved from Italy to a developing country.

During the Centre's early years, ICTP's budget was also in question.

The Italian government had authorised more than US$275,000 a year

for the first four years of ICTP's operations. Moreover, the land

and structures that were part of the Centre complex were valued

at more than US$2.5 million.

IAEA, in turn, initially budgeted US$55,000 annually for the Centre

(rising to US$150,000 in 1967). This represented a generous contribution

given the Agency's modest budget yet broad-ranging responsibilities

that reached far beyond scientific research and training to include

efforts to promote peaceful applications of nuclear energy and

the creation of inspection teams to curb nuclear proliferation.

However, those who examined the Centre's mandate--including a

Consultative Committee of Experts appointed by IAEA's director

general and the Centre's own Scientific Council--all agreed that

ICTP would need an annual budget between US$500,000 and US$750,000

to fulfil its mandate.

As a result, the Centre in the 1960s was continually searching

for money to bring its resources closer in line with its vision.

The Ford Foundation, which awarded ICTP a four-year US$200,000

grant, helped to make up the difference. Nevertheless, the funding

was not permanent and there was no guarantee that it would continue.

Partially due to its provisional status and budget uncertainties,

the Centre did not have a permanent research staff. Instead it

relied on visiting and guest scientists and professors of the

University of Trieste (who acted as consultants) to meet its research

and training needs.

Like many working for ICTP's administrative staff, scientists

at the Centre actually belonged to other institutions, coming

to the Centre during periods when university classes were not

in session or at a time when they were on sabbatical leave.

Visiting professors during these early years included A.O. Barut,

University of Colorado at Boulder, and Christian Fronsdal, University

of California at Los Angeles, USA. During ICTP's first academic

year, 1964-1965, each stayed for 10 months to organise and participate

in training activities for younger scientists.

Similarly, Marshall N. Rosenbluth, University of California, San

Diego, USA, and Roald Z. Sagdeev, head of the Plasma Physics Laboratory,

Institute of Nuclear Physics, Novosibirsk, USSR, came to Trieste

to help launch the plasma physics group. Rosenbluth's and Sagdeev's

partnership--indeed friendship--helped to make ICTP one of the

few places in the world where scientists from the East and West

could work side-by-side during the Cold War.

In addition, such prominent institutions as Princeton University

in the United States, Imperial College in the United Kingdom,

CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in Geneva, Switzerland,

and the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna, USSR, allowed

their staff scientists to come to the Centre for several months

each year, providing a steady stream of world class scientists.

Despite all of the vagaries and unknowns, ICTP flourished during

the first decade of its existence thanks to the drive of Abdus

Salam and the enthusiastic support of the word scientific community.

The efforts laid a foundation for success that quickly earned

the Centre international acclaim.

ICTP's first scientific activity was a four-week International

Seminar on Plasma Physics, held in October 1964, which attracted

such eminent scientists as Boris B. Kadomtsev, USSR Academy of

Sciences' Nuclear Energy Institute, and W.B. Thompson, Clarendon

Laboratory, UK. The Centre's second scientific activity, a two-month

Seminar on High Energy Physics and Elementary Particles, which

took place in May and June 1965, included future Nobel Prize winners

Murray Gell-Mann, Sheldon Glashow and Julian Schwinger.

Seminar on High Energy Physics and Elementary Particles, June 1965

And then there was the star-studded Symposium on Contemporary

Physics held from 7 to 29 June 1968--an event that put ICTP on

the global scientific map serving as the 'symbolic' foundation

stone of its scientific activities.

Werner Heisenberg lectures during the Symposium on Contemporary Physics, June 1968. Paul A.M. Dirac (in background) chairs session

The symposium, which was attended by nearly 300 scientists from

some 40 countries, brought 21 current and future Nobel Prize winners

to Trieste. Among the scientific luminaries in attendance were

Hans A. Bethe, Francis H.C. Crick, Paul A.M. Dirac, Werner Heisenberg

and Eugene P. Wigner. The gathering marked the arrival of ICTP

as a world class research centre dedicated to cutting-edge issues

in physics and with the capacity to attract the world's most talented

scientists. The symposium also indicated the Centre's emergence

as a prominent crossroads for scientific exchange.

Besides the workshops and seminars, there were three extended

courses (two in nuclear physics and one in condensed matter physics),

each with some 100 participants and each lasting from 10 to 12

weeks. The courses, which included introductory lectures during

the first week and examinations of the most recent advances in

the field for the remainder of the time, attracted young physicists

from developing countries and developed countries alike. The latter

were not financially supported by ICTP but were eager to come

nevertheless.

Building on the success of these noteworthy activities, by the

end of the 1960s, ICTP had attracted more than 1500 scientists

from 55 countries.

At the same time that the Centre was earning a well-deserved reputation

for research and training excellence, it was also launching what

would become its flagship programme: the Associateship Scheme,

which enabled scientists from the developing world to visit the

Centre for extended periods three times over a three-year period

(later extended to six years).

The ultimate goal was to allow scientists from the South to remain

at home yet to be fully engaged in cutting-edge science. Among

the Centre's first Associates were Juan Jose Giambiagi (Argentina),

Riazuddin (Pakistan), Igor Saavedra (Chile), and Daniel A. Akyeampong

(Ghana), each of whom went on to have distinguished careers in

science and science administration in their home countries. Over

the years ICTP has selected more than 2000 Associates.

In less than a decade the Centre had indeed laid the foundation

stones--both symbolically and concretely--for its success. As

a result, ICTP ended the 1960s as an institution proud of its

rapid progress and cautiously optimistic about the prospects for

growth and maturity in the 1970s.

Paolo Budinich

ICTP Deputy Director, 1964-1978